journal | team | miscellany | home

Bear Aware

Rick White

A decade of declining enrollment. The prevailing anti-intellectual political climate. Escalating tuition costs. A nationwide student loan crisis. The whole STEM craze.

In the fall semester of 2020, when I enrolled in the prestigious creative writing MFA program at the University of Montana, there were plenty of good reasons to suspect the school might not have my best interests at heart. Even before the global pandemic gutted budgets and emptied classrooms, the writing — for universities in general, for the humanities in particular — was on the proverbial wall. Of the more than two million bachelor’s degrees awarded by American postsecondary institutions in 2019, fewer than 40,000 went to English majors — an astounding number even to those of us with tumbleweeds tossing around in the left brain space where the math neurons are supposed to be. More astounding yet: somehow that number was down 27% from 2012. But if I harbored any anxieties about returning to campus to pursue another arts degree of questionable economic value, those fears were assuaged the day before classes began, when I received my first e-mail alert from university police.

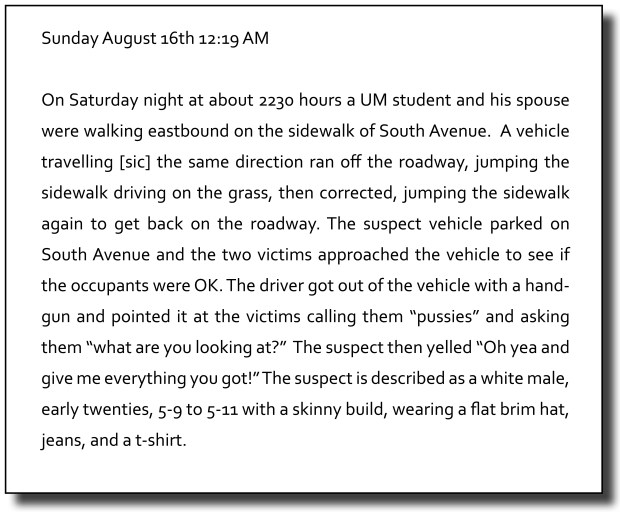

I had spent ten years shuffling through the glamorous career options available to someone with degrees in human geography and environmental studies. I had tended bar, wrangled middle schoolers, and driven a bread delivery truck. By the time I decided at age 37 to become a UM Grizzly once again, I had worked my way up the late-capitalist labor ladder to the eminent position of cellarhand at a local cidery, where I stacked kegs and swept floors for twelve bucks an hour. So, perhaps I was a bit overeager to begin the comparably pleasant work of analyzing prose. Reading that first alert, though, I couldn’t help but appreciate the elegant stylistic choices made by its anonymous author. In the space of one single, action-packed paragraph, the reader is given vivid details that render a dramatic scene. We get characters in conflict. We get blended diction, high and low. We get stakes. Of particular literary note, the author of this pithy missive displays a keen ear for dialogue. They seem instinctually to know just how and when to use quotes to reveal character. I mean, could the person who yells “pussies” and “what are you looking at?” and “Oh yea and give me everything you got!” really be anyone but a skinny white boy in a flat brim? Sure, in haste the author made a few spelling and grammatical errors, but enough to diminish the quality of this tidy piece of mid-length e-prose? Not for this first-year MFA. In one brief emergency alert, this talented wordsmith had accomplished everything I was about to pay good money to learn how to do.

The next morning I pedaled my ancient bicycle to school feeling eager and full of hope. I sailed the six blocks down leafy University Avenue and onto campus. There I bumped along the brick walkway to the Oval, a vast manicured field flanked by Romanesque brick buildings, a life-sized bronze statue of a grizzly bear, and, to the east, towering behind Main Hall, the rounded Mount Sentinel of the Sapphire range. The Oval was absent the flying frisbees and loitering undergrads who usually adorn its grassy expanse. Five months into the pandemic, though, empty public spaces were more common than not. I rode on.

To keep myself protected against death and disease, I went first to the auxiliary gym and picked up my complimentary Healthy Griz Kit: two maroon face masks with university logo, one bottle hand sanitizer with university logo, one bottle spray sanitizer with university logo, one gray terry cloth towel — oddly sans university logo. I then paid my tuition bill, along with an additional $1,288.00 in mandatory campus fees for the semester, and tried to silence the doubts I had about it being money not well spent. In my two classes — a nonfiction writing workshop and a lit seminar on the novels of Samuel Beckett and Virginia Woolf — I experienced the usual back-to-school butterflies in the stomach, nerves both tempered and exacerbated by the masks worn and social distances observed. I could hide, which was nice, but I had trouble being heard. No longer was I anxious, though — not about the quality of the education I was paying to receive, and certainly not about some pop-gun-waving punk on the lam. Everything, it seemed, was going to be just fine.

And it was — it was just fine. For the first few weeks, we met outside for class, lounging in the lush green grass (Facilities Fees: $74.00) while soaking up warm September sun and brilliant modernist prose. My professors were exceptional — intelligent, witty, sensitive, well-read — despite being comically overworked due to cuts made to administrative and janitorial support. My peers were just like me, only smarter and no so long in the tooth. They enjoyed reading canonical works of Western literature; they felt passionately about a book’s artistic merits or faults; and they believed, like I do, that a well-crafted sentence possesses a mystical ability to both illustrate and intimate the human condition.

Given the restrictions necessitated by the pandemic, I did not exercise at the pristine rec center or swim laps at the pool (Campus Recreation Fees: $130.00); did not take notes from PowerPoint presentations in so-called smart classrooms (Technology Fees: $83.00); did not attend Grizzly football or volleyball games, which had been cancelled (Athletic Fees: $73.00); and did not meet classmates in the University Center for homework sessions over coffee or snacks (UC Fees: $145.00). I wrote at home, I read at home, and I conversed in person, outside, for six hours each week.

Still, for the first time in years, I felt like I was part of something meaningful. No longer a mere cog in the technocorporate machine, I had found my place. I was once again a valued member of a community of learners.

▪

SIGNS OF TROUBLE BEGAN TO APPEAR near the end of the first week. A wildfire raced up Mount Sentinel and blackened a good chunk of its face before fire crews could contain the blaze. Two weeks later, smoke from larger fires farther west settled into the Missoula valley, and for a week my classes retreated to Zoom. The one time I meandered onto campus during that dismal week, the place emanated the eerie apocalyptic aura of widespread involuntary depopulation — like, say, Detroit post-bankruptcy, or like most of rural America after the rise of Walmart and Monsanto. But not once did I feel in danger or seriously concerned — not, that is, until a few weeks into the semester, just after the date passed to withdraw from classes with a refund.

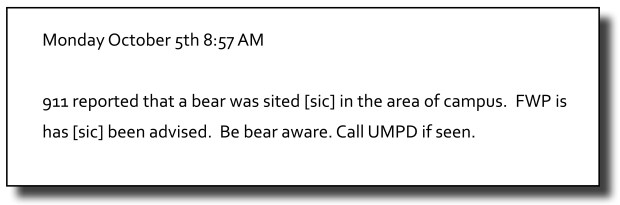

Now, on most college campuses, or even “in the area” of them, a bear sighting would elicit a bit more, I don’t know, alarm? It would certainly warrant an emergency alert with more than four simple, declarative, typo-riddled sentences, one of which (“Be bear aware.”) was as deficient in helpful instruction as it was efficient in the economy of its prose. But this, I reassured myself, is has Montana. Our sports teams are known as the Grizzlies for a reason, are they not? The authorities at Fish, Wildlife & Parks had been properly alerted, had they not? What’s more, the author of the UM emergency alerts had long since earned my readerly trust. So when their message said in effect, Hey, somebody saw a bear last night, but it’s just a bear, no big deal, that is precisely how I took it. Just a bear. No big deal.

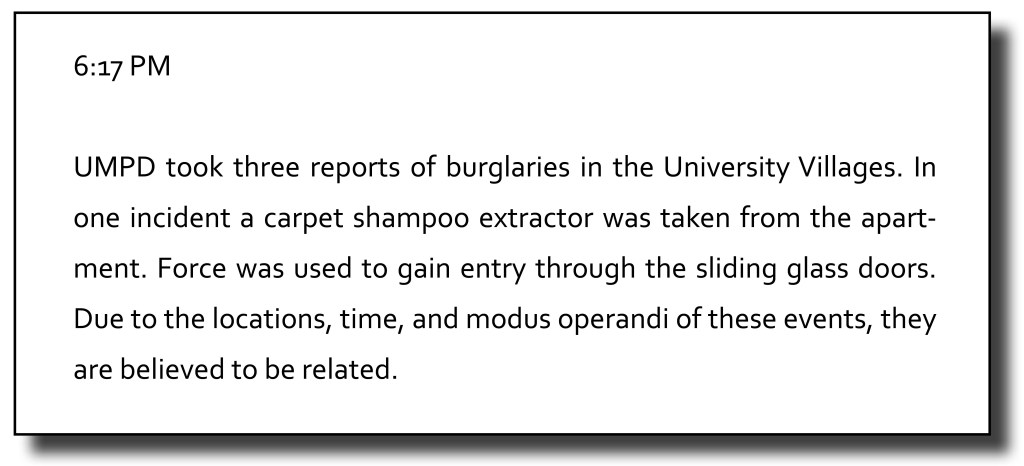

Oh, the desperation a person must feel when considering their options and deciding that the best is to drill into a dormitory washing machine and steal the handful of quarters therein. Your heart goes out to them. Maybe they just needed some beer money. Or perhaps they had missed the date to withdraw with a refund. Whatever their motivation, the disturbing part of this particular alert was not the burglaries but rather the fact that I received notice of them twice. Now, why many UM students and faculty members are issued two, sometimes three university e-mail addresses is a mystery that confounds me. Notwithstanding, sometime in early October, someone in some administrative office somewhere on campus got their e-hands on an e-spreadsheet with my second university e-mail address on it, then proceeded to enter that address into their e-alerts database. Not only that, they got my cell phone number, too. On Monday the 19th, I received not one but three identical alerts of more robberies gone weird.

That’s right: modus operandi. Nothing like an archaic Latinate criminology term to spice up the theft of a glorified Shop-Vac. Really gets the blood pumping. Especially on the third read.

Imagine the thrill I got one morning later that week when I was jolted awake by the frantic smartphone triple vibration of the following e-mail/e-mail/text message alert:

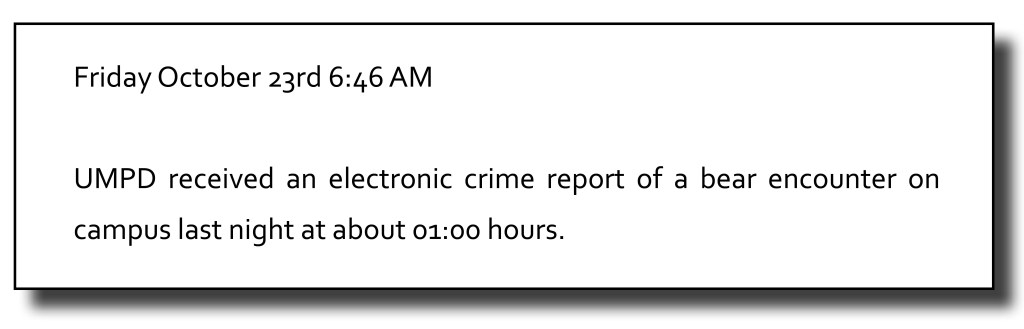

Come again? A crime report? At 01:00 hours? Well, shit, that escalated quickly. In just a few short weeks, we had gone from bear siting [sic] in the area of campus to bear encounter on campus proper. And not just a casual encounter, mind you, but one whose description suggests that the bear was perpetrator of an unspecified crime. Assault and battery? Grand theft auto? Might a bear preparing for hibernation have use for a carpet shampoo extractor?

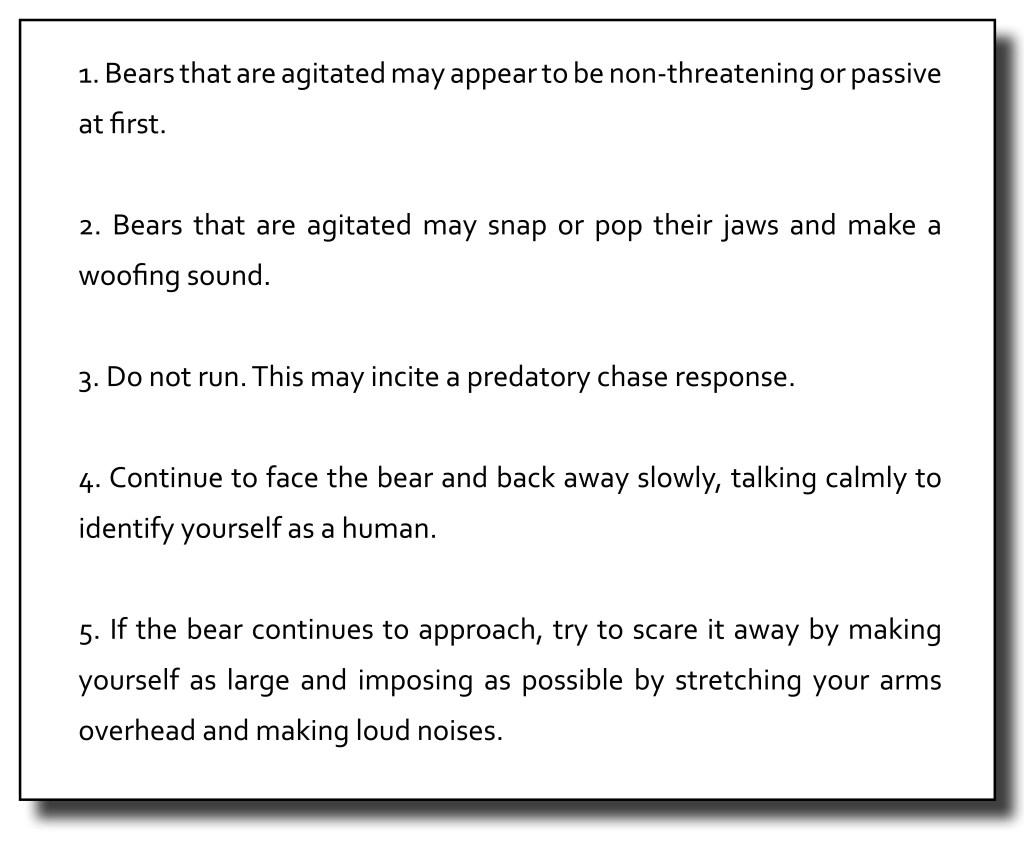

I suspect the author of the UM alerts received helpful feedback on their first bear-related alert, for in this message they got more specific about what it means to “be bear aware.” To the end of the message, they affixed a five-point list of helpful “safety tips for bear encounters”:

Now, non-threatening and passive are not the two adjectives that first come to mind when I picture an agitated bear snapping and popping its jaws at me, but no matter. By the end of October, I was hardly on campus anyway. Cold weather and low light had forced us off the lawns and online into cold, rectangular Zoom rooms. The chances of me needing to back slowly away from a woofing bear while performing a cacophonous sun salutation were, by that time, slim to none. While it was nice to finally see the unmasked faces of my peers and professors on the screen, any sense of personal connection to campus I may have developed was abruptly severed. If the fallen leaves of deciduous trees carpeted campus in glorious reds and golds, I never saw them. I logged on at the proper meeting times using the proper links and passcodes, thereby resigning myself to the gloom of my part-chosen, part-imposed new curricular reality: online graduate school for the price of a real life college education.

▪

NOT TO WORRY, THOUGH. As any novelist will tell you, sometimes there comes a point in the writing of all good stories where the subplot becomes more interesting than the primary narrative. Often it ends up subverting the plot line for good.

During the first week of November, UMPD alerted us to three separate reports of bear sightings: on Sunday near the tennis courts, on Monday by the “M” trail parking lot, and on Saturday “in the area of UM Greek Houses on Gerald Avenue.” In those three alerts, the officers efforts’ at bear conflict meditation went from “actively attempting to trap the bear” to “lost sight of it” to “relocation efforts are still underway” — a shift in tone that displays all the rhetorical slipperiness of a Donald Rumsfeld press conference. Clearly, in attempting to usher this rogue bear off campus, mistakes were made. I half expected the next alert to be the photo of a banner flying triumphantly on the clocktower of Main Hall: “Mission Accomplished.”

By the time that third bear alert of the week came buzzing in, buzzing in, and buzzing in again, my tether to non-screen-mediated reality had seriously begun to fray. My hygiene suffered at least as much as my mental health, descending to the ditch-filth level of one of Sam Beckett’s absurdist clown tramps. I wore sweatpants exclusively, the one pair I owned. I stopped showering more than necessary — say, once every couple of weeks or so. The two-block trip to the laundromat became an expedition of daunting proportions — impossible, impassable, not even worth attempting.

Fortunately, my cohort brought me back from the edge of the abyss. In a group text with classmates, my friends evinced a rather hopeful read of the bleak predicament in which we found ourselves, an interpretation quite different from my own. Where I saw institutional ineptitude, they found excitement and strong narrative potential. Specifically, they began to root for our new campus protagonist, a classic antihero in the Dostoyevskian mold. “Loving the evolution of BearWatch 2020,” my friend Sam texted. “He’s done with his classes so he’s headed to Greek row to party.” To which my buddy Emmett replied, “He’s following a classic college trajectory — start at the library, then check out what it’s like to be a frat bro. By the end of the year he’ll be smoking American Spirits and talking about post-structuralism.”

The next week, the UM alerts author ratcheted up the rising action even more. On the 10th, the alert was not just of a bear, but of a “large” bear — presumably a black bear, not a grizzly, but without the clarifier, how was one to know? On the 12th it was “a large bear and a small bear.” On the 14th, it was a large bear again, spotted near a dorm. UM’s finest searched the area, but reported that they were unable to locate the large bear.

Later that morning, I called my parents in Arkansas to check in and say hi. My dad answered. “Better look out for those bears,” he said.

“No shit,” I said. “What, did the school put it on the website or something?”

“Oh, no,” Dad said. “Text message alerts. You must’ve put me down as an emergency contact or something. Been blowing up my phone for months.”

▪

THE FINAL BEAR ALERT of the pandemic-abbreviated fall semester arrived on the Monday of finals week.

Missing prepositions. Improper spacing. Inconsistent usage of the singular and plural. It could have been that the training I was receiving in advanced literary analysis was causing me to find deep meaning in even the shallowest of texts, but upon receiving this alert, I grew concerned for its author, in whose prose I had long since staked my readerly faith. Either these two dumpster-diving fugitive bears posed a more critical threat to the university’s pic-a-nic baskets than I had thought, or COVID isolation had taken its toll on more than just us students.

By the time I turned in my final seminar paper, I had spent the lion’s share of three full months either staring at printed words on a page or gazing into the harsh blue light of an 11” MacBook Air — all while confined within the walls of a four-hundred-square-foot apartment I shared with my girlfriend and our two dogs. My eyes were wild and bloodshot. My beard was ratty and matted. My long, graying hair was disheveled and unkempt. I felt, looked, and surely smelled like a wild animal trapped in a cage.

And to think: I was just an amateur. A first-year grad student writing to a small audience of sympathetic professors and like-minded peers. How much more bearish the pressure on the person charged with composing all those UM emergency alerts, who by circumstances far beyond their authorial control had unwittingly become the voice of a flagship institution of higher education, whose message reached far beyond the borders of one quaint, mid-sized college town — some two thousand miles to Arkansas and beyond.

I suppose we should have seen it coming. Before lockdowns and Zoom rooms, before empty classrooms and ghosted Ovals, the crisis in the humanities was on the wall for all to read. At colleges across America, students and professors of the arts, fine and liberal alike, had become the beleaguered mascots of an education system in shambles. Then, in 2020, we got shunted off to some so-called “asynchronous modality,” a semi-virtual space that, far as I can tell, now exists indefinitely somewhere between Main Hall and my greasy laptop screen.

In our place on campus, the bears came in and made themselves at home — and the bastards didn’t even make them pay tuition and fees.

▪ ▪ ▪

Rick White’s work has been published in Lit Hub, The A.V. Club, High Desert Journal, Westword, and Camas, and nominated for Best American Essays. He earned an MFA in creative nonfiction from the University of Montana in 2022. He now does campus communications work for a university in the Upper Midwest. The irony of the situation is not lost on him.

journal | team | miscellany | home