Casebook Home | Twelve Winters Miscellany

Earliest Drafts of the Story

Ted Morrissey

To give some sense of the evolution of “Vox Humana,” I’ve gone back to the earliest draft of what would become that short story. Like most of what I’ve written, creatively, what it began as and what it became are significantly different. My creative process is very much one of discovery. I don’t plan ahead. I just start writing, trusting that, eventually, the process will take me somewhere useful and (hopefully) interesting.

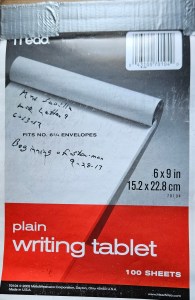

Many years ago I began writing my creative work — mainly fiction — longhand, as opposed to writing via typewriter (when I began) or word-processor (later) or computer. At some point, while working on what would become my first published novel (Men of Winter, 2010 — but finished much earlier than that), I began writing exclusively in Mead 6 x 9-inch tablets. I like the size. It is easy to handle and manipulate while writing in the chair I always sit in. More important is the fact the small, handwritten page looks nothing like the page when it’s typed and printed. I find that when I compose on a computer screen (as I’m doing this very moment) I’m aware of how sentences and paragraphs look, which then influences how I’m putting the words on the screen (or paper, back in the typewriter days).

I want to be focused on the words and sentences and paragraphs regarding their meaning and their potential effects — not on their appearance on the page.

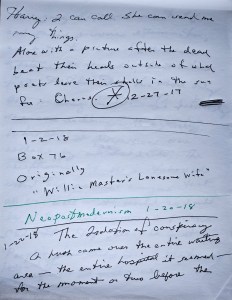

The story that would become “Vox Humana” spans four Mead writing tablets, beginning with one marked as “Mrs Saville / mid Letter 9 / 6-13-17 / Beginning of Star-man / 9-28-17.” When I started using this particular tablet, I was working on Mrs Saville, an epistolary novel, and I was in the middle of “Letter 9,” as of June 13, 2017. Some three and a half months later, I began work on what would become “Vox Humana” (on September 28, 2017). I first thought of the piece as “Star-man.” I always pick a title that seems appropriate, knowing, though, that I will change it before finishing whatever it is.

(In the photo, you’ll note the strips of duct tape binding the top of the tablet. Mead used to make their tablets of sturdier stuff, but at some point they became flimsier, so flimsy that pages would easily become detached. I began wrapping the tops of the tablets in duct tape to fix this issue. It became a kind of ritual: readying a fresh tablet for whatever creative adventure it may facilitate by securing its unblemished pages in strips of gray duct tape.)

In 2017, I published the novel Crowsong for the Stricken, which is set ostensibly in 1957, in the Midwest. After finishing Mrs Saville, I had a desire to return to the world of Crowsong and write some new stories. I thought I might write a few more; then release a new edition of Crowsong with the added material. The year 1957 had resonated with me because it was the year of Sputnik 1, the first artificial Earth satellite, launched into orbit by the Soviet Union’s space program on October 4. It was obviously a watershed in human history, and it had a profound impact on the psychology of Americans. I wanted to tap into that mélange of complicated emotions: wonder, awe, envy, disorientation, fear. It rattled Americans’ sense of their country as being superior to every other, but especially their arch rival, the USSR. At the same time, we were enthralled by Sputnik as we followed its path overhead. The period is sometimes referred to as “the Sputnik Crisis.”

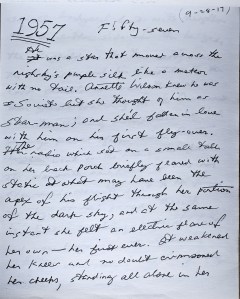

Even though the launch of Sputnik and its impact on the American psyche supplied the creative kernel that fueled the writing of Crowsong for the Stricken, there wasn’t an episode in the novel that spoke directly to the event. So when I decided to return to the novel’s world, I thought I might, finally, write a story about Sputnik’s launch and how it affected specific characters. When I started composing, it seems I was considering three related titles: “Star-man” or “1957” or “Fifty-seven.” Annette Wilson, the upper-grades English teacher who appears briefly in Crowsong for the Stricken, appealed to me as a character whose fleshing out may yield something interesting.

I brought Mrs. Wilson and the idea of the Sputnik crisis together to begin the narrative. I combined elements of Sputnik with elements of another event, equally shocking, that happened a few years later: the Soviets’ first manned launch into space, Vostok 1, piloted by cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, on April 12, 1961.

As you will see, though, the concept of the story, having to do with either Sputnik or Vostok, was ultimately abandoned, and it evolved into something quite different. Nevertheless, there are certainly traces of “Vox Humana” even in these earliest drafts. I have tried to transcribe the written draft accurately.

Mrs Saville / mid Letter 9 / Beginning of Star-man / 9-28-17

1957 Fifty-seven (9-28-17)

It He was a star that moved across the nightsky’s purple silk like a meteor with no tail. Annette Wilson knew he was Soviet but she thought of him as Star-man; and she’d fallen in love with him on his first fly-over. Her The radio which set on a small table on her back porch briefly flared with static at what may have been the apex of his flight through her portion of the dark sky, and at the same instant she felt an electric flare of her own—her first ever. It weakened her knees and no doubt crimsoned her cheeks, standing all alone in her small backyard but with neighbors close on either side of the hedges, the Reynoldses to the west, and Mr. Robinson and his daughter to the east. Annette sensed them all in their yards watching for the Cosmonaut and then returning indoors when he had quickly passed from view. Annette, however, went to the radio and felt its warmth, sent to her from the sky. It had passed through her like a crackling wave of heat and now lingered in the Sylvania, with its oversized knobs and glowing dial.

She poured a glass of rose and sat for a long while sipping her wine and resting her hand on the radio, which was tuned to a country station out of Crawford, but really the music was Star-man’s, set directly and passionately to her. Every song was a lovesong, even the breakup songs and the ones about Jesus.

—

—

The Soviets said there was no one aboard its craft that kept circling the earth, but everyone was skeptical. Annette Wilson was more than skeptical: she knew better. She could feel her Star-man as he streaked across the sky, could sense his thoughts, knew what lay in his heart. A knewfound joy was glowing in hers like a piece of uranium. Her students detected it, as if armed with geiger counters. They had been studying the morose poetry of Poe—they spent a whole morning on ‘Annabelle Lee’—and then Mrs Wilson suddenly shared Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Love Sonnets from the Portuguese. Mrs. Wilson had typed them herself, and the sheets were pungently moist, <still> fresh from the Mimeograph machine. She began by reading aloud from her typescript. Her voice was clear and she articulated every syllable with care; however, when she read sonnet XXVII her voice waver with emotion and her eyes became glossy with welling tear behind her tortoise shell glasses.

My own Belovéd . . . . .

Mrs. Wilson’s students were nonplussed. They had never known their teacher to become so emotional—sentimental and queerly enthusiastic about the literature she loved, yes, but not emotional to the point of weeping in class.

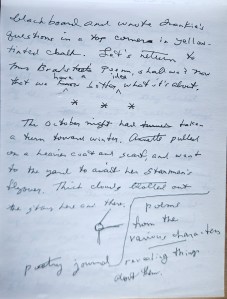

Beforehand, Mrs Wilson had written a list of poetic devices and | 10-3-17

[End of memo pad]

Starman cont’d 10-3-17 / > / became Vox Humana

(list some)

their definitions on the blackboard. When she was finished reading, she had her students work with a partner to identify techniques in the poems. Meanwhile, their teacher worked at composing herself.

. . . . . .

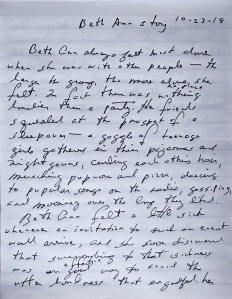

[Many pages of writing followed this section, exploring a lot of different ideas about the story, including bringing in some of her students as significant characters, especially Frankie. I also considered various experimental techniques, including somehow structuring the story like a satellite [there’s a conceptual sketch]. Meanwhile I was searching through stories from Crowsong for the Stricken for ideas and inspiration, especially “The Curvatures of Hurt.” There are no dates throughout this section, which means I wasn’t typing up the pages because I knew the story didn’t yet have its footing. It’s worth noting that much of this material became fodder and inspiration for the story that immediately followed, known at first as “Beth Ann story,” which I began October 2018 and completed January 2019. It was published as “The Cold Dark March to Winter.”]

. . . . . . .

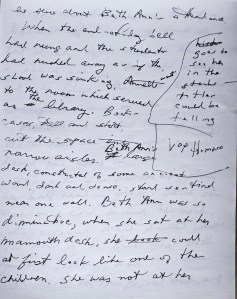

Annette composed poems and little stories when she was a child, but by the ti her teen years she’d gotten out of the habit. The War effort was all-consuming—collecting scrap metal, writing letters to the wounded trips [troops], co consoling the mothers whose sons were away being soldiers. There was no room for soppy verse. Over the years she had thoughts about [?] poems she could write, but something always prevented her from touching pen to paper and getting the words down in ink. Something inside of her that she never bothered to name. It was like fear, but not fear of inadequacy, fear that her words were not good enough—fe more like fear of exposing some interior part of herself <psyche>, a piece she kept hidden even from herself.

| snap shots of Annette Wilson’s life | Brother in Korea

—

—

Her brother, Harry, came back from Korea in ’53, but he wasn’t the same person who’d left. That Harry was confident, enjoyed a good joke, and loved being outdoors. He’d thought about selling farm equipment or seed—something that would keep him out of the <an> office, <traveling the road>, and meeting people. This new Harry was different in almost every way. He’d returned from the Korean conflict in one piece, physically, but something had happened to his mind

Harry hadn’t written for more than a year, or at least none of the letters had gotten through; Then out of <the> blue he called, and said he was in South Carolina, he was taking a train, then a bus and hed’ he’d be in Crawford at the Greyhound terminal in three days—could Annette <or Tim> pick him up? Tim and the car had been gone for three weeks and two days at that point. It was too complicated to explain over the phone, especially long distance, so Annette said she would see her brother then.

. . . . . .

[From this point the story developed into the final version of “Vox Humana.” The above material and several pages that followed it were finally typed up 11-18-17. In my handwritten pages, an asterisk inside a circle, along with a date, is my notation for having completed typing a given section on that day. Via marginal remarks, one can see at which point different ideas regarding the story came to me: “translation school”; “[Sandburg’s] War Poems 1914-1915”; “Relief of Tim’s departure … from her feelings of inadequacy”; “Armed Services Edition”; “Harrison Gale”; “Taejon ? looks like Trojan (War)”; “he goes to the store, has some sort of flashback”; “faces like a Greek chorus”; “How about a section in the form of a Greek play? The climax?”; and “Vox Humana” [I recall I’d read the phrase vox humana somewhere about this time, and I immediately fancied it as the title for this story; unfortunately I don’t recall where precisely I encountered the phrase].

[The story was continued in the tablet identified as “‘Vox Humana’ cont’d / 12-15-17 / The Isolation of Conspiracy cont’d / 1-22-18”; and its conclusion was marked with an asterisk-circle on 12-27-17. Note: “The Isolation of Conspiracy” was the working title of what became the novel The Artist Spoke (2021); also, the reference to “Box 76” dated January 2, 2018, is a reference to the William H. Gass Papers at Washington University in St. Louis — I must have been planning a trip there to do research for a paper (which I was scheduled to present at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture in February).]

I want to emphasize that the earliest drafts were not a waste of time. Not at all. They helped me get my bearings for what would become “Vox Humana.” Also, much of that material went into the next story I was to write, which I thought of at first as the “Beth Anne story” but ultimately changed to “The Cold Dark March to Winter.”