journal | miscellany | press | podcast | team

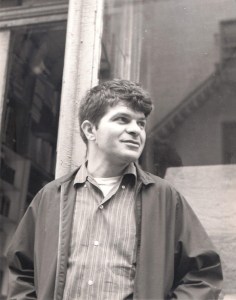

Gregory Corso’s Forgotten Harvard Education

Kurt Hemmer

[An excerpt from the work in progress The Poem Human: A Biography of Gregory Corso]

In notes for an abandoned memoir, Gregory Corso wrote, “meeting b lang in ptown bar; 1954 again in village she with now wellknown painter, invites me to cambridge mass; the car ride up; learning of her inevitable young death to come; not believing her because death seemed incredible to me then.” That car ride would dramatically change the trajectory of his life. He arrived in Cambridge encouraging the young, elite students to see him as a hipster ex-con. He left as a harbinger of the poetry to come.

Violet Ranney “Bunny” Lang had become particularly close to Frank O’Hara when he was at Harvard in 1947. She would appear in his poems “An 18th Century Letter” (dedicated to V. R. Lang), “V. R. Lang,” “A Letter to Bunny,” “A Party Full of Friends,” “A Step Away from Them,” “The ‘Unfinished,’” and “To Violet Lang.” O’Hara recalled, “I first saw Bunny Lang … at a cocktail party in a book store in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She was sitting in a corner sulking and biting her lower lip—long blonde hair, brown eyes, Roman-striped skirt. As if it were a movie, she was glamorous and aloof. The girl I was talking to said: ‘That’s Bunny Lang, I’d like to give her a good slap.’” Though they never did get around to it, O’Hara and Lang were going to write a cantata together. “She was a wonderful person,” wrote O’Hara. “She is one of our finest poets.”

Through Bunny, Corso became close to O’Hara. In 1957, O’Hara would write in his poem “To Hell with It,” “memories of Bunny and Gregory and me in costume / bowing to each other and the audience …” Quite often, when Frank thought of Bunny, he could not help but think of Gregory. He writes of being in Paris hoping to find Gregory “in the Deux Magots because I want to cry with him / about a dear dead friend.” Gregory seemed to have a knack for getting Frank out of his depressions. O’Hara writes in “The ‘Unfinished,’” “I’m not depressed any more, because Gregory has had the same / experiences with oranges, and is alive.” Corso remembered, “Oh, I liked Frank an awful lot. I remember the first time I heard something from Frank O’Hara was in 1954 at Harvard—a poem about a tiger leaping over the table and pissing in the flowerpot as he leapt over. I thought that was great, just that one line.” It was actually five lines from “Chez Jane.”

O’Hara found Gregory attractive. He wrote that if an earthquake buried Corso, Gregory was “too lustrously dark and precise, he would be excavated and declared / a black diamond and hung around a slender bending neck.” Like he had done with Bunny, Frank would take on the role of older brother with the handsomely dark poet who liked to remind anyone who would listen that he had recently been in prison. O’Hara eventually became an assistant curator at the Museum of Modern Art. One could sniff the rarefied air of the New York art world coming off his sport coat. An esteemed member of a select group, he was admired by most people who even slightly knew him. Ironic and amusing, his poetry sometimes read like the journal notes of an insouciant prodigy. Of all the New York School poets, which included John Ashbery, Barbara Guest, Kenneth Koch, and James Schuyler, O’Hara would become closest with the Beats. “Yet O’Hara,” explains literary critic Marjorie Perloff, “had none of the revolutionary fervor, the prophetic zeal of the Beats.” Nonetheless, he was the poet most convivial with Corso, other than Gregory’s Beat friends. That is, of course, if you also excluded Bunny Lang.

In “Getting to the Poem” Gregory stated, “I have lived by the grace of Jews and girls.” Allen Ginsberg was certainly one of the Jews by whose grace Corso lived. One of the first “girls” to help Gregory by her grace was Bunny. Of all the major Beat writers, Corso, perhaps surprisingly, had the best relationships with artistic women. Unlike Ginsberg and Burroughs, who tended to ignore female artists, and Kerouac who generally interacted with women simply for sex or to find a mother figure, Gregory had several important relationships with female artists. He had an appreciation for women that is generally ignored by most commentators.

Lang was brilliant and magnetic. She had been an editor of the Chicago Review while a student at the University of Chicago. A published poet and a promising playwright born with a silver spoon in her mouth to match her silver (and often sharp) tongue, Bunny, according to her friend Nora Sayre, was “[a] formidable presence, she had harsh blond hair, heavy jaws, and wide, expressive nostrils; her whispery, guttural voice could coil from a sexy growl to a parody of prudery.” Gregory met Bunny in a Provincetown bar in 1953 and saw her again in the Village in 1954 when she was chasing around the painter Michael Goldberg. Bunny’s and Gregory’s friend Dick Brukenfeld thinks they likely saw each other again in the Village at one of Ginsberg’s parties. Poet Kevin Killian wrote, “Like Ginsberg, Lang claimed to have had personal experience of ecstatic Blakean visions—waking dreams—that left her alert to beauty in all corners of life, and a taste for the louche.” Gregory was just her type. She came to New York in January 1954 to see her play Fire Exit performed by the Artists’ Theatre at the Amato Opera Theatre on 159 Bleecker Street. The play reflected Lang’s stint as a stripper in Boston at the Old Howard. In 1949, Bunny’s mother had died. This lack of a mother provided even more common ground between her and Corso. Her 1952 play Fire Exit, based on the Eurydice and Orpheus myth, appealed to Gregory’s fascination with Greek mythology. In 1954, Bunny brought him to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she was the secretary of the Poets’ Theater, which would produce three of her plays. Sayre, who knew Corso in Cambridge when she went to Radcliffe College and was part of the Poets’ Theatre, wrote, “Finding [Corso] destitute in New York, Bunny brought him to Cambridge and passed the hat among the cast and crew.” He would become a favorite mascot of the now legendary Poets’ Theatre.

Even after the Beats gained notoriety, Sayre, who became a film critic for The New York Times and was nominated for a National Book Award for Sixties Going on Seventies (1973), did not warm to the Beats. Nora admired the Beats’ enthusiastic rebelliousness and their refreshing irreverence, especially while she was revolting against her own privileged upbring. But she could not identify with the Beats’ glamorization of drugs, their romanticization of mental illness, and their sentimental spirituality. Bebop jazz was not her thing. She found Burroughs’s Junkie, published under the pen name William Lee, compelling and a little terrifying, but found it hard to finish Kerouac’s On the Road. Sal Paradise, Kerouac’s persona in his most famous novel, came across as a naïve child to Sayre, and his romanticizing of Blacks in America seemed ridiculous to her. She also did not like the Beats’ misogyny. Their lives, she determined, were much more interesting than what they wrote. She also had to shoo off Gregory every time she tried to eat a BLT sandwich in front of him because he always tried to steal her bacon.

According to Bunny’s friend Alison Lurie, who privately published a memoir of Lang financed by the poet James Merrill in 1959, Bunny “was of medium height and rather heavy, with firm, fair, heavy flesh. Her hands were broad, with short fingers; her face molded in low relief like a face made in clay by a child. There was something childish too in the full pout of the mouth and the placing of the rather round eyes …” Though her physical appearance made it seem unlikely, Lang was enchanting. Lurie wrote, “In the early days of the [Poets’ Theatre] most authors were already Bunny’s friends or lovers or hoped to be.”

In the Lower East Side, Bunny had what Lurie describes as a “violent affair” with Michael Goldberg, a second-generation Abstract Expressionist painter whom Corso befriended. The two men shared a deep appreciation for jazz. Goldberg was one of New York’s subterraneans. Like Gregory’s old flame Marisol Escobar, he had studied with Hans Hofmann at the School of Fine Arts. Goldberg became friends with Willem de Kooning in the late 1940s and then with O’Hara in 1952. Frank and Mike would collaborate with one another in 1960. Goldberg was featured in O’Hara’s famous poems “Why I Am Not a Painter” and “The Day Lady Died.” One of the poems Gregory greatly admired was O’Hara’s “Ode to Michael Goldberg (’s Birth and Other Births).” At the San Remo Cafe, Frank had introduced Bunny to the seductively bohemian Mike, whom O’Hara championed as one of the best artists of his generation. The relationship between Lang and Goldberg was tempestuous. When Goldberg travelled to Boston in April 1954 to ask Lang’s father for her hand in marriage, the anti-Semitic Mr. Lang was having none of it. Bunny was also suffering from the complications of Hodgkin’s disease, and the overwhelmed Goldberg sought solace in the arms of painter Joan Mitchell. In October 1955, Lang received the Vachel Lindsay prize from Poetry magazine for her play I Too Have Lived in Arcadia. Brad Gooch wrote of the play, “It’s action concerns a bucolic life of goatherding led by Damon and Chloris—obviously Goldberg and Lang—until interrupted by Phoebe—obviously Mitchell—a painter and old girlfriend of Damon’s from The City, who lures him back.” After her romance with Goldberg failed, Lang wrote the play I Too Have Lived in Arcadia, which has been called “Beat-inspired” and includes a “talking dog with Beat vocabulary.” Bunny’s play was a dig at Goldberg, who had rejected her after they had been engaged. Beat scholar Ronna C. Johnson suggested that Lang’s writing prefigures the Beats more than the New York School poets.

In 1958, Goldberg married a strikingly beautiful writer, Patsy Southgate. Then he appeared in the January 29, 1959, issue of Time, which displayed a black and white photograph of him and his painting Summer House in color. Modern American art authority David Anfam noted Goldberg’s “deep affinity with his era’s heterodox poetics—notably propounded by his New York School friend, Frank O’Hara.” The poet and art critic David Shapiro appreciated Goldberg’s “fabulous sense of scale, the fury of his multiple works, and the ways in which this work seemed to have the optimism of O’Hara’s most libertine sequences.” Goldberg took over Mark Rothko’s studio at 222 Bowery in 1962, where he would work, live, and die while painting in 2008. It was in the same building that would later house the “Bunker,” Burroughs’s residence in the 1970s.

The Venice West poet John Thomas, a close friend of Charles Bukowski, wrote of meeting Mike and Patsy on December 11, 1962, at a party thrown by Donald Allen: “Mike was a well-known New York ‘action painter.’ He and the missus (whose name I forget) were the dedicatees of Gregory Corso’s hilarious poem ‘Marriage.’ They were very ‘Noo Yawk.’” Most admirers of Corso’s “Marriage,” his most famous poem, do not know that when it was originally published in the Summer 1959 issue of Evergreen Review it was dedicated “for Mr. and Mrs. Mike Goldberg.” In autumn 1964, Goldberg was admitted as a psychopathic personality to the Psychiatric Institute at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, the same institution Ginsberg had been placed in during the 1940s. Like Ginsberg, Goldberg had chosen the Psychiatric Institute rather than go to jail. He had stolen several of de Kooning’s unfinished drawings, signed de Kooning’s name on them, and sold them. This incident ended his marriage to Southgate.

“Marriage,” the poem dedicated to Mike and Patsy, was Corso’s signature poem and one of the greatest poems of its era. In readings it provided comic relief to Ginsberg’s “Howl.” Ostensibly about whether the speaker should get married or not, the poem also revealed his conception of what it meant to be a poet. Thus, it became a poem not about whether anyone should get married but if an authentic poet should get married. And what was an authentic poet to Corso? A true poet was a romantic figure who wooed women in graveyards, like Shelley did to Mary on the grave of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft. He would be wearing a “velvet suit” and a “faustus hood.” The Romantic poet of Corso’s imagination resembled himself creating new, previously unheard combinations of words, like “werewolf bathtubs.” The words “penguin” and “dust” appear side by side in this poem likely for the first time in the history of literature. The problem with marriage was its predictability. How the parents reacted, how the ceremony went, how various types of couples behaved. And if there was one thing the Romantic poet was not it was predictable. Thus marriage, though possible, seemed unlikely. The end of the poem references the novel She (1887) by H. Rider Haggard. Though rarely read today, the best-selling novel has never been out of print and inspired eleven adaptations into film, the first being a short by Georges Méliès. A favorite of Henry Miller, the novel is about an adventurer and his ward journeying to a lost African kingdom ruled by Ayesha, She-who-must-be-obeyed. The queen believes the ward is the reincarnation of her lover, who has been dead for two thousand years. It seems possible that Corso might have come across this novel at Clinton Prison, but there is no direct evidence of when or where he discovered it.

There were rumors that when Bunny, Mike’s old flame, lived in the Village “she had been a witness in a murder trial, and had once been picked up by the police for soliciting for prostitution, some said as the result of a bet.” Lurie, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Affairs (1984), believed, “She was the most important or most violent experience they would ever have for a great many people; how many, no one can guess. During the seven years I knew her, at least twenty men and women loved her intensely in their various ways.” Bunny had several affairs while she knew Gregory, but there is no evidence that she had one with Corso.

Bringing him to Harvard, for Lang, who had disdain for academia, was her way of dropping a pack of burning firecrackers into the middle of campus. Sayre related, “Corso then spent a year camping out in a couple of Harvard houses; to most of the New Critical section men he appeared as a symbolic threat to Harvard’s traditions, an explosive device that might fragment custom and usage: the hipster language he imported was utterly new to Harvard Square.” He both shocked and inspired the students he encountered. According to Sayre, “[P]lanting Corso in Cambridge was probably a deliberate act of sedition. No one at Harvard—not even the New Yorkers—had met anyone like him, and [Bunny] took him to starchy gatherings and urged him to be insolent … [S]he foresaw Corso’s impact on the community—where his style and idiom became contagious for some restive undergraduates.” In Cambridge, he fell right in with the Harvard boys and Radcliffe girls whose backgrounds differed tremendously from his own. Fitting in fast had become one of his skills, probably honed while in prison. What few, if any, of them would recognize was that Corso was part of the wave of the future. The historian David Halberstam, whom Dick Brukenfeld knew as a fellow occupant of Dunster House at Harvard, would dedicate an entire chapter to the Beats in his best-selling The Fifties (1993): “[T]hey consciously rejected this new life of middle-class affluence and were creating a new, alternative life-style; they were the pioneers of what would eventually become the counterculture.”

Insecure about his own lack of formal education, Corso established his intellectual legitimacy by emphasizing his Harvard and Radcliffe connections. His acceptance by the offspring of the blue bloods provided him with a coterie of like-minded, culturally engaged youth. In later years, said George Scrivani, Corso was proud to say that when he dropped the name of someone famous that it “bounced.” He did not envy or deride the rich; he took them as they came. And when it came to his innate talent, he was not only accepted but admired by his privileged comrades, though they did not understand him when he spoke to them about the new “hipsters.” He wrote to Isabella Gardner in 1958, “I remember too how ‘wrong’ people were about me there; at the Poets Theatre when they asked me to explain ‘hipster’ to them, mostly under [Bunny] Lang’s insistence, that the hipster was a new soul in America … this hipster is fated to make a permanent change in the literary firmament of America. This at the time was laughed at, yet was indeed quite prophetic.” What separated Bunny from her peers was her recognition of Corso as some kind of new street prophet.

Her poetry, unlike her friends’, had been in The Chicago Review and Poetry, which gave her some clout among the Poets’ Theatre crowd. The driving force behind the Poets’ Theatre was its vice president, Molly Howe (aka Mary Manning), a playwright, novelist, and film critic from Ireland who had once worked with William Butler Yeats. Her daughter, Susan Howe, became a distinguished poet. “And since Yeats and Synge had been able to revolutionize the theater in Dublin early in the century and in equally threadbare circumstances,” wrote Sayre, “[Molly Howe] felt that something similar should be possible in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the Fifties.” The president of the Poets’ Theatre was Lyon Phelps and it was founded in 1950, after a discussion instigated by Richard Eberhardt, a Harvard professor, at his home. The Poets’ Theatre was loosely run at various times with the help of Eberhardt, Hugh Amory, John Ashbery, John Ciardi, Edward Gorey, Donald Hall, Alison Lurie, William Matchett, George Montgomery, Frank O’Hara, Richard Wilbur, and William Carlos Williams.

For a time, W. S. Merwin was associated with the Poets’ Theatre, which had invited Dylan Thomas to give his first American reading of Under Milk Wood. The first American production of Samuel Beckett’s All That Fall would be performed by the Poets’ Theatre, as well. Dame Edith Sitwell and her brother Sir Osbert Sitwell would also appear under the aegis of the Poets’ Theatre. “The objective,” recalled Sayre, “was to generate work by poets who would act, administrate, direct, and sell tickets—while retaining total control of their own writing … the goal was the emergence of an American verse theater.” In time, the Poets’ Theatre would gain a substantial reputation.

The rebellious nature of the poets associated with the Poets’ Theatre prevented them from embracing their association as if it were some sort of unified group. According to Sayre, “[Richard] Wilbur said the Poets’ Theatre was like the Communist Party: everyone belonged to it, but no one wanted to admit it.” The group went out of its way to separate itself from the polished competence of Broadway and the members enjoyed being a little gritty. “And although Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery were gone from Cambridge while the theater was developing,” Sayre believed, “the conversational, anecdotal style of their early poetry influenced some of the playwrights who wrote in a formless fashion—which was the fashion of the time.” The first evening of the Poets’ Theatre was in 1951, and after some members of the audience sniggered at O’Hara’s Try! Try!, which Bunny directed and appeared in as the character “Violet” with John Ashbery as the character “John,” Harvard’s visiting lecturer, Thornton Wilder, chastised the audience at intermission. Before it all fell apart, the Poets’ Theatre would perform plays by Cid Corman, Lawrence Durrell, Richard Eberhardt, Paul Goodman, Ted Hughes, Kenneth Koch, Archibald MacLeish, James Merrill, Howard Moss, Louis Simpson, Peter Viereck, and Robert Penn Warren.

Lang made the Poets’ Theatre a respite for Corso, though he sometimes had to sweep to earn his keep. He even had a walk-on part as a madman in one of their productions, The Changeling by the Jacobeans Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. “But no one except Bunny,” Sayre admitted, “could appreciate what would soon be a voice of the immediate future.”

Bunny married the painter Bradley Phillips on April 15, 1956, who would posthumously publish Lang’s book The Pitch (1962). Tragically, she would die of Hodgkin’s lymphoma at the age of thirty-two on July 29 of that year. Lurie wrote, “For months [after her death] we would find ourselves … thinking how she would laugh when she heard that Gregory Corso had actually—and then remembering that she couldn’t laugh, because her mouth was full of earth.” Her death would be devastating to both Frank and Gregory. When Bunny died, O’Hara wrote, “it would have been no sacrifice / to give my life / for yours.” Corso’s “For Bunny Lang” appeared in the sixth issue of i.e. The Cambridge Review in December 1956: “I see a dead music / pursued by a dead listener.”

Corso’s life in Cambridge, which can be credited to Lang, has rarely been discussed in depth by scholars of the Beat Generation. His relationship with Bobby Sedgwick, the brother of Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick, has been particularly glossed over. It would be through Corso’s connections at Harvard and Radcliffe that his poetry and plays first garnered attention. Brukenfeld, who was later a theater critic for The Village Voice, said of Gregory, “He was very focused. He knew who he was and what he wanted. A lot of us were not as secure in that knowledge, certainly not at that age. He knew what he needed to do to be successful, and a big part of it had to do with charming people to help him.” Bobby’s older sister, Alice Sedgwick Wohl, known to her family as “Saucie,” wrote, “[Bobby] and Peter Sourian had an exotic waif called Gregory Corso living secretly in a tent in their room. You cannot imagine what a sensation Gregory created in Cambridge. He was a street kid still … Somehow he had found his way to Harvard, and there he was, writing poetry and living from hand to mouth among the privileged, who couldn’t get enough of him.” Alice was one of those who was charmed by Gregory when she visited her brother.

Corso developed a connection to the Sedgwick family, through Bobby, that would last many years. Alice recounts, “I got to know Gregory when he was living in a tent in the room that Bobby and Peter Sourian shared in Eliot House … and [Gregory] was around all the time, just tagging along. I remember his talking a lot about the poetry that he was reading, most particularly Shelley, who was his hero in life and in art.” To many students at Harvard, he was a larger-than-life and authentically romantic figure. Brukenfeld recalled, “We adopted Gregory Corso our senior year at Harvard. Three of my fellow students kept him in their Eliot House rooms for the 1954-55 school year. They hung a tie-dyed sheet across a corner of their living room to give Gregory a place to sleep. They brought back bowls of food from the dining hall to sustain him.” According to Brukenfeld, “Bobby Sedgwick, Paul Grand, and Peter Sourian took [Gregory] in and that was the relationship. I think the main person in that group who initiated that and everything was Peter Sourian, who was close to Bunny Lang.” Sourian, author of the novel Miri (1957), would be become a professor at Bard College.

Sourian’s friend, Bobby Sedgwick was remarkably handsome and vain, often admiring himself with a pocket mirror. On the surface, he was an all-American, Ivy-League, big-man-on-campus with a promising future. Brukenfeld believed that Corso had an influence on Bobby “in a general sense.” But Alice, Bobby’s sister, disagrees, “No—it was the other way round if anything. Gregory was just part of Bobby’s break with the conventions of our family. It may be relevant that Bobby was connected to a journal …” As one of the editors of the third issue of i.e. The Cambridge Review, Bobby published Gregory’s poem “Requiem for ‘Bird’ Parker.”

Though the general narrative has been that Ginsberg was responsible for making Corso into a Beat poet and was responsible for helping Gregory get published, the opposite is true. Gregory tried hard to help his Beat friends get published before they became famous. He did not see himself at this point as in Allen’s shadow. Corso had his own connections. Bobby, who was friends with the other students working on i.e. The Cambridge Review, was one of Gregory’s best connections. Calling Kerouac “Buddhafish,” Gregory wrote to Jack on September 22, 1956, “ie. the cambridge review has asked me to edit their winter issue. I will. I will definitely want all Jack (Ordained Buddhafish) Kerouac’s LUCIEN MIDNIGHT!!!!!! Or else some poems.” “Lucien Midnight,” Kerouac’s most experimental prose work, was published as Old Angel Midnight (1973). Ginsberg reminded Kerouac to send Corso prose or poems in October, and told Jack that Corso was trying to publish their friends Philip Whalen and Gary Snyder, but Corso failed to convince the editors to publish Kerouac and Snyder. Gregory had also used his clout at i.e. The Cambridge Review, unsuccessfully, to try to publish works by Burroughs, Ferlinghetti, and Rexroth. Had the journal taken Corso’s advice, the issue, which already included the New York poets Koch, Ashbery, and O’Hara, would have been one of the watershed publications of the 1950s. Yet, the sixth issue of i.e. The Cambridge Review did include Ginsberg’s poem “A Dream Record,” which appeared, along with two poems by the San Francisco Beat Philip Whalen, because of Gregory’s influence. “A Dream Record,” which Ferlinghetti would cut out of Howl and Other Poems, was a catalyst for Allen’s memories of friends in “Howl.” In this early version of “A Dream Record” in The Cambridge Review, Ginsberg used the name “Lucien,” which Carr demanded be removed from future publications of the poem because he did not want to be associated with the Beats’ controversial public image.

Bobby, who would do much to help Gregory’s fledgling career as a poet, had a nervous breakdown in his sophomore year in the spring 1953 and had to be removed from campus in a straitjacket. He returned to Harvard in the fall 1953, and Corso’s arrival at Harvard in the fall 1954 was a breath of fresh air for him. Bobby had a stifling relationship with his father, Francis Minturn Sedgwick, Sr. In a posthumously published poem, Corso mentions, “when I was 24 / I was riding on Duke Sedgwick’s bike / A ten speeder; fell flat on my back.” “Duke” was the nickname of Bobby’s father. This suggests that Gregory had more interaction with the storied Sedgwick family than has previously been known. Though Bobby’s sister, Alice, was quick to tell me, “[M]y father never had a bicycle; that must have been Bobby’s bike.” She recalled that in the summer of 1955:

“Gregory and his ‘wife’ as he called her, a seraphic girl from the South called Sura, came to visit my first husband and me at a house we had rented for the summer on Cranberry Island. They stayed a couple of weeks and I remember them reading and reciting poetry every evening, and whenever we went sailing Gregory would put a volume of Shelley in his pocket in case he drowned, in memory of Shelley, who drowned with a volume of Keats’s poems in his. Both Gregory and Sura were rather childlike and very very sweet.”

George Scrivani remembers seeing Corso, later in life, casually interacting with Edie’s younger sister, Susanna “Suky” Sedgwick, as if they were old acquaintances. Alice told me, “Suky met Gregory years later in San Francisco in Haight-Ashbury, perhaps even in the ’80s, but meanwhile he had certainly met our sister Edie with Allen Ginsberg in New York in the mid-60s.” In 1966, Gregory, who did not like Warhol and blamed him for Edie’s descent into drugs, confronted Warhol, who was sitting with Ginsberg at Max’s Kansas City:

“I know you, mister, and I don’t like you … I know all about you pop people … How you use people. How you make them superstars of New York and then you drop them. You’re evil … Too many lonely women are in love with you. You use them. You give them dope and then you leave them. You don’t love them … I’m glad I’m not in your faggoty scene. It’s all show. I see that beautiful blond angelic face of yours and it’s got a snarl on it. It’s an ugly face.”

According to Sourian, “[Corso’s relationship with Bobby Sedgwick] brought out the best in Gregory—which was his gentle side. Bob once said to me, ‘You know, he soothes me.’” Corso helped Bobby remove himself from the oppressive shadow of his father. “I loved Bobby …” said Gregory. “He was a very moody person. Very moody. And stuck on Zen Buddhism, which was the thing that helped cool him. He was the first person I ever saw get into Zen …” This might be surprising to scholars who assume Corso got his first taste of Zen from Ginsberg or Kerouac. Bobby also taught Corso an important lesson: “When I went to Harvard, I suddenly learned that rich kids do not have it better than others. They’re still locked into something. I was coming from the cold prison and these people were coming from the warmth of a six-thousand-acre ranch, but, good God, they still can’t get out!”

Corso’s influence might have helped Sedgwick find a new identity. Radical politics became an interest for Bobby, he dated a beautiful Black woman, and he started using the vernacular of the hipster. Unfortunately, he could not get out from the menacing shadow of his father. In 1963, he was placed in Bellevue, then Manhattan State Hospital, and then the Institute for Living in Hartford. When he got out and returned to Cambridge, he had a lovely Mexican girlfriend, a black leather jacket, and a Harley-Davidson. On New Year’s Eve 1964, he crashed his bike into a bus trying to beat a light on Eighth Avenue in New York. There was speculation of suicide. He remained unconscious in the hospital until he died on January 12, 1965. His father combined his ashes with those of his brother, Minty, who had committed suicide by hanging himself in March 1964, and went to a high ridge alone where he “opened the box and, jerking it into the air, scattered his sons’ ashes to the winds.”

For Bobby, Gregory seemed to have emerged miraculously from a completely different world. Sayre shared, “One of our producers [at the Poets’ Theatre] sometimes referred to Corso as ‘the black poet’—due to the blackness of his hair, his periodic scowl and his disdain for detergents, also his black garment … So the epithet wasn’t intended as a compliment. But when Corso overheard it he was delighted: ‘Yes! I am! I am … the black poet.’ Thus, Corso became “the black poet” of Cambridge. Sayre relishes telling her readers, “[I]n the dining hall [Gregory] once informed Archibald MacLeish, ‘You’re not a poet!’ Corso gave different reasons for having been in jail: sometimes he said he’d been sentenced for starting a bookstore with stolen books.” Though Corso liked playing the “bad boy” with MacLeish, he also respected the former Librarian of Congress and author of the famous poem “Ars Poetica.” Corso agreed, “Like Archibald MacLeish said, ‘A poem should not mean, but be.’” He also fondly recalled sitting in on MacLeish’s class at Harvard: “He’d sit there like the White Father, you know, people laughing, reading their poems, criticizing each other. I just went to one because he invited me up there …” There was another interaction between “the black poet” and the revered Harvard professor. Corso wrote to Ginsberg, “If you didn’t write and live a great poem before your 30th year give up. I told that to [Archibald] MacLeish, and he sent me away from Cambridge. Goodbye, Gregory Corso.” MacLeish didn’t literally banish Corso from Cambridge, but one can understand the professor’s ire over Gregory’s remark considering that it wasn’t until MacLeish was thirty-one when he gave up his job as a lawyer to move to Paris to dedicate himself to his craft. Corso’s favorite MacLeish poem was “Not Marble or Gilded Monuments,” published when MacLeish was thirty-eight. It is a poem that denies that what a poet loves can ever be made immortal but that the moment of recognition of beauty is what is important. As late as September 1957, Corso was having nightmares of MacLeish: “I saw Archie MacLeish before me sitting in a huge leather wheelchair, his hands were of stone and on them were carved winged heads of seraphim.” But, in general, Corso liked MacLeish and Harvard. He recalled, “I wrote … a play, In This Hung Up Age, all about hipsters and beat people, long before any of this Beat nonsense came to light, and the play reviewed in the Crimson was said to have been the best play of the year there; and Roger Shattuck [a Harvard lecturer who won the National Book Award in 1975 for Marcel Proust] came up to me and told me he liked it very much.” The scholar Kevin Killian, who refers to Corso as Lang’s “protégé,” wrote, “Under her tutelage Corso wrote In This Hung-Up Age,” though he provides no hard evidence to back up this claim.

In This Hung-Up Age, written in 1954, which would become his first published play when it appeared in Encounter’s January 1962 issue, was performed at The New Theatre Workshop on April 28, 1955. Johnson referred to Corso’s plays as “surrealist-beat poets theatre of the Absurd.” In This Hung-Up Age would later be published in New Directions in Prose and Poetry 18 in 1964 and in The Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater: 1945-1985 in 2010. The play, which is Corso’s most accomplished work of drama, is an allegory that takes place on a Greyhound bus. Three days out of New York and heading for San Francisco, the bus breaks down. The story becomes a lampoon of hipsters, rednecks, liberals, struggling poets, and college students. It absurdly ends with the bus being trampled by a stampede of buffalo, a nod to the mistreatment of the Native American passenger throughout the work. The only survivor, apropos of Gregory’s romanticism, is Beauty, a nonspeaking part, who is a saxophone-playing young woman zonked on sleeping pills. “The language of his characters is fast vigorous, and funny, and the denouement is grotesquely original,” wrote the Harvard Crimson.

In his 1963 note on his play, Corso stated, “I can safely claim that this play, indeed document, pre-dates anything ever written about Hipster and hip-talk, the Square, and the advent of San Francisco’s ‘poesy rebirth’ … I was truly a hipster, the only hip thing to do was laugh that silly vision straight in the face, and I did.” He had written nearly the same thing to Laughlin in 1961 when he was trying to get a book of his plays published by New Directions. Still insecure about his position in the Beat world, Corso wanted to make sure that credit was given where credit was due. He believed that he was the first true hipster of American drama.

On July 20, 1978, introducing his reading of his play Sarpedon at the Naropa Institute, Corso claimed, “In 1954 I wrote it—24 years ago—that’s when I first hit Harvard. Mr. [John H.] Finley, [who was Master of Eliot House and a Harvard faculty member], a great Greek scholar, was running Eliot House and I was told by one of his TAs, if I could write a Greek play I could stay at Eliot House. I did it overnight.” Brukenfeld questioned this: “My understanding is that Finley and the other Eliot House officials didn’t know of his presence at Eliot House at first. It took a while for his existence as a stowaway there to be known. It makes more sense that after he was established there and known as an avid-for-knowledge poet, one of Finley’s assistants would give him the challenge of writing a Greek play in order to stay.”

Whatever the case, Gregory was proud of this play. He described his inspiration for Sarpedon: “Like the great Greek masters, I took off where Homer left an opening … My opening was found in the Iliad. Sarpedon, son of Zeus and Europa, died on the fields of Troy, and Homer had him sent up to Olympus with no complaint from Hades, who got all the others that died there. Thus I have Hades complain …” Sarpedon would be published in a stand-alone edition edited by Rick Schober in 2016 by Tough Poets Press and in 2021 in Collected Plays. The play reads like the first act of what would have been a strong three-act play. Sarpedon has gone to Olympus after dying on the field of battle. Hades wants Sarpedon for his domain and is enraged. A hipster-speaking Hermes shows up. Believing that Zeus, disguised as Hector, has seduced his wife, Persephone, Hades assaults Aphrodite. Hades had mistakenly believed that the goddess of love was Zeus’s wife, Hera, and he wanted revenge. Displaying Corso’s love for the Iliad, Sarpedon is intelligently witty. Reading the play helps us understand why his Harvard and Radcliffe friends thought of him as a prodigy and wanted to help him.

A few Beat novels had already appeared, The Town and the City (1950) by Jack Kerouac (under the name John Kerouac), Go (1952) by John Clellon Holmes (under the name Clellon Holmes), Junkie (1953) by William S. Burroughs (under the name William Lee). As far as poetry, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Pictures of the Gone World was published on August 10, 1955, and Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems was published on November 1, 1956. But when Gregory Corso’s The Vestal Lady on Brattle and Other Poems was published in May 1955 it was the first book of Beat poetry.

No one knows for sure how many copies of the first edition of The Vestal Lady on Brattle exist or were even printed. Brukenfield, the publisher, says it was three hundred copies. A few of the poems in the volume had been previously published: “In the Early Morning” in The Harvard Advocate, “In the Tunnel-Bone of Cambridge” and “Requiem for ‘Bird’ Parker” in i.e. The Cambridge Review, and “King Crow” in Audience. Corso’s first interview and book review appeared in The New York World-Telegram and The Sun in Murray Robinson’s 1955 article “Gregory Sends Us Poems that We Don’t Get.” Robinson wrote that Gregory was a “slum kid” he had discovered the previous year writing poems in a tunnel. Corso told Robinson that his poems came from the soul, not reality. Robinson wrote, “Most of [The Vestal Lady on Brattle and Other Poems] I’m sure will be huzzahed by the type people who say they understand progressive jazz and abstract painting.”

The Vestal Lady on Brattle is dedicated, “For all my friends … my beautiful Cambridge friends.” The introduction, signed P. L. B. by David Wheeler, who had helped critique and edit Corso’s poems, stated that Gregory “is simultaneously conscious yet remains fluidly child-like.” The brief author bio mysteriously said that he “expects to extend his commutation to Lovelock, Nevada.” Though the volume claims that the poems therein were written in Cambridge between 1954 and 1955, we know that Gregory claimed that he wrote at least one poem in the book, “Sea Chanty,” his first poem, when he was fifteen or sixteen years old.

Brukenfeld wrote, “[Corso] received no money beyond one symbolic dollar. None of us were paid—not me for publishing the book, not Nick Cikovsky for designing the cover, nor Harvard teaching fellow David Wheeler who wrote the introduction under the pseudonym ‘P.L.B.’ All money went to the printer who delivered our edition of 300 copies in mid-May.” Corso argued, “When I publish this book, Vestal Lady, … you look at the best seller list of the time and you see that the novels of that time aren’t even known today, whereas this still gets published because the poems are taught in colleges and high schools … Whereas those other pieces of shit that got all these people millions of dollars came and went.” The best-selling novels in The New York Times Book Review for May 15, 1955, were John P. Marquand’s Sincerely, Willis Wade, Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, Mac Hyman’s No Time for Sergeants, C. S. Forester’s The Good Shepherd, and Robert Ruark’s Something of Value.

The Vestal Virgins of his book were the priestesses of Vesta, the goddess of home and family, who protected the sacred fire of Rome. They were the most trustworthy and incorruptible women in the city; in short, they were the very opposite of what Gregory thought at the time of his mother. If the Vestal Virgins let the sacred fire extinguish, if they jeopardized the home of Rome, they were to be beaten. The Brattle Street of the title is the most important thoroughfare in Cambridge, which Corso would frequently explore.

He presents himself unabashedly as a hipster in the volume. The poem “In the Tunnel-Bone of Cambridge” has him calling himself “a subterranean” who listens to Gerry Mulligan and uses phrases like “play it cool.” Throughout the book he uses words like “chick,” “sticks of tea,” “payote [sic],” “digs,” and “kick.” “The Horse Was Milked” is presciently about shooting heroin, a drug that he had yet to use: “Deep in the night he rolled and groaned / O never was a poor soul so stoned.” His poem “Requiem for ‘Bird’ Parker, Musician” is full of hip language, like “nowhere,” “wail,” “draggy,” “square,” “man,” “goof,” “split,” “bugged,” and “crazy.”

But the defining feature of the volume is violence, especially involving children and mothers. In the title poem, the vestal lady is a witch. She spies a child on the street: “Despaired, she ripples a sunless finger / across the liquid eyes; in darkness / the child drowns.” Another tragic child appears in “Dementia in an African Apartment House”: “A bullet-holed lion excited the dying child.” “The mass silence deafens the last echo of a happy child,” in “Coney Island.” In “Greenwich Village Suicide” a storekeeper washes the sidewalk of blood after a woman plunges to her death. “In the Morgue” depicts a corpse like a child being lifted by an embalmer acting as its mother. “Sea Chanty” is about a mother killed by the sea and her child eating her washed-up feet. “Song” is about taking the pig’s daughter to the slaughter. “In the Early Morning” has a rapist with “bloodstained fingernails” stalking a runaway. “In My Beautiful … and Things” Corso wrote, “not like a mother or a bitch.” “Your mother came today. Did she say hello?— / —No—,” Corso wrote in “Dialogues from Children’s Observation Ward.” In “You, Whose Mother’s Lover Was Grass” Corso lamented, “you shall be orphaned to an asphalt city.” It is suggested in “The Sausages” that the meat is made from the butcher’s daughter’s feet. A girl is pursued by a stalker as her mother calls after her in “The Runaway Girl.” If, as Mark Van Doren had criticized, there was too much mother in Corso’s destroyed “Prison Poems,” there was certainly plenty left for The Vestal Lady on Brattle.

In the final poem, “Cambridge, First Impressions,” Corso admitted, “But my lie makes awkward the gait.” As usual, he feels he doesn’t belong. He has come to Cambridge to experience visions, like Herman Melville, but they have not come: “I’ve walked Brattle lots these days, / and not once did I catch from out the dark / a line of light.” But he has experienced enough pleasure to make the experience worthwhile, and he will take these memories with him on his next journey: “I can go to books to cans of beer to past loves. / And from these gather enough dream / to sneak out a back door.” The Harvard sojourn had been auspicious.

Though the limited number of copies prevented the book from receiving the critical attention it deserved, a few key people took notice. It was included in a review of young poets published in the October 1956 issue of the prestigious journal Poetry by the poet Reuel Denney. “Would these poems sound interesting,” asked Denney snidely, “only if conveyed by a co-axial speaker into an audience already ‘far out’ on jazz, done in the throw-away-the line style of Bebop styles of articulation?” Little did Denney know that Corso was sounding a clarion call for a poetry of the near future that would be prominent in little magazines for the next decade. In a more favorable, unpublished review, O’Hara wrote, “Corso is also the only poet who, to my taste, has adopted successfully the rhythms and figures of speech of the jazz musician’s world without embarrassment and with a light, musical certainty in its employment.” He thought of Corso as “one of our leading young poets” and felt that “one of his greatest skills, a perfection of brevity which few contemporaries can rival …” Frank could hear where Gregory’s style was going. A change was in the wind.

Corso’s father, Joe, wrote to “Sonny,” the name he always used for his second son, on June 9, 1955, care of Paul Grand at Eliot House, D-21 at Harvard. In later years Grand would become a distinguished lawyer and marry the daughter of Manhattan D.A. Robert Morgenthau, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s mentor. Joe’s letter was forwarded to Gregory at the Kettle of Fish bar at 114 MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village. Joe wrote:

“We were so thrilled about the first book you sent, needless to say when your book of poems arrived this week, well—I was so proud I showed the whole shop and boss as well … Jerry [Corso’s half-brother] wants to be a trumpet player … Between a poet and a trumpet player we should be very famous someday, eh! … I am very proud of you. Keep trying.”

On June 29, Kerouac wrote to Ginsberg about a meeting he had with Viking Press editor Keith Jennison and editorial consultant Malcolm Cowley. Cowley was the Lost Generation chronicler who knew and had been friends with nearly all the American expatriate writers of 1920’s Paris. It would be Cowley who helped revive William Faulkner’s reputation in the 1940s, and who would eventually help Kerouac publish On the Road. Jack reported to Allen that the esteemed Cowley had asked, “‘You know a poet called Gregory Corso?’ It seems Gregory has put out a book of poems and making big hit, The Lady of Brattle Street or something like that.” Ginsberg responded on July 5, “I don’t understand Corso’s celebrity. I saw a poem of his about [Charlie] Parker … in Cambridge Review. But I still don’t understand what or how he’s doing that Cowley knew him … Yes, Gregory must be conning? For what who? … My drear penmarks—I wonder if they helped or hindered Gregory’s development.” What Ginsberg did not understand was that Corso did not need his help at all.

In Kerouac’s next letter to Ginsberg, July 14, Jack’s tone had changed. Gregoy had written a poem for Jack called “Buddha,” and now Kerouac seemed giddy over his friend’s success. “Corso’s celebrity obtains from enclosed POEM book which I send you,” he wrote to Ginsberg, “hold it for me. Nice inscription. Also, he wrote a play which he was going to entitle Beat Generation, changed to This Hungup [sic] Age when he saw my New World shot [“Jazz of the Beat Generation” published in April 1955 by Kerouac under the name Jean-Louis]— … big hit, he got big write ups … Gregory makes big hit with Boston socialites.” If Kerouac still thought Corso was encroaching on his territory, he didn’t say it. Holmes had used the term “beat generation” first in his novel Go (1952). Explaining its significance in a New York Times article in November 1952, Holmes credited Kerouac as coining the phrase. Further evidence that Corso had already embraced being a “Beat” while in Cambridge is found in the contributors’ bios of the first issue of the journal i.e. The Cambridge Review in Fall 1954. He is listed as “a young poet [who] has retreated from New York to Cambridge to finish his novel on ‘the beat generation.’” That such a novel possibly existed, possibly as a very rough draft, is given credence by a letter to Ginsberg from Kerouac in late June 1955 in which Jack wrote, “Gregory also to show his novel to Cowley.” Whatever became of this “novel” has been lost to time. Few people outside of Corso’s friends would have known what the “beat generation” was. It would not be until after the “Howl” trial and the publication of On the Road in 1957 that the Beat Generation gained national recognition. Corso’s contributor’s bio in autumn 1954 is strong evidence that he had already created an identity for himself that involved an indelible attachment to Kerouac, Ginsberg, and the burgeoning Beat movement.

There was still some controversy to be had. Brukenfeld remembered, “What happened was [The Vestal Lady on Brattle and Other Poems] didn’t sell. The stores essentially returned them. They didn’t want them. People weren’t that interested after [Corso’s] time in Cambridge. He called me from California and accused me of taking money and all this, which was absolute nonsense. There was no money to take.” In 1969, City Lights made a facsimile edition of The Vestal Lady on Brattle and Other Poems just as Brukenfeld had published it. Brukenfield explained, “We’re talking independent, casual publishing here, not corporate. Neither Ferlinghetti nor City Lights ever contacted me to seek permission to re-publish Vestal Lady. Don’t know where New Directions came into the pic, but they never contacted me either. So I never received any royalties from the City Lights edition …” He was not bitter, just stating the facts. “Here’s my end of the story …,” wrote Brukenfeld. “Gregory calls me from the west coast accusing me of stealing the profits from the book sales. There were next to no sales … After the effort I’d made to help a friend, I didn’t need him screaming accusations of theft at me. I too had a temper. . . . so pissed off I sent [some 70 books] collect. Gregory never picked them up. A year or so later they came back to me.” According to Brukenfeld, “And then [Gregory] went to City Lights Bookstore, took a copy of the book that we had published, that I had published, and City Lights copied it. They made an exact facsimile of that book The Vestal Lady on Brattle and they essentially republished it.” In 1976, City Lights would print an edition that combined The Vestal Lady on Brattle with Corso’s second book, Gasoline (1958), the volume that would permanently tie him to the Beats.

▪ ▪ ▪

Kurt Hemmer is the editor of the Encyclopedia of Beat Literature and a Professor at Harper College. With filmmaker Tom Knoff, he produced several award-winning short films on Beat poets. His essays have appeared in Naked Lunch@50: Anniversary Essays; A History of California Literature; Beat Drama; The Cambridge Companion to the Beats; Approaches to Teaching Baraka’s Dutchman; William S. Burroughs: Cutting Up the Century; The Beats, Black Mountain, and New Modes in American Poetry; and Harold Norse: Poet Maverick, Gay Laureate. He organized The Jack Kerouac Centenary Conference, is currently the Secretary of the Beat Studies Association, and is working on a Gregory Corso biography.

journal | miscellany | press | podcast | team