journal | miscellany | press | podcast | team

Commentary on

“Mirror, Mirror in the Text …”

Sante Matteo

It was an actual email that started the process that led to the hybrid hodge-podge resembling a Platonic dialogue in the form of a series of comments and replies to a Facebook post.

That particular email, one of many that I receive daily from Academia.edu, on whose site are posted several of my academic essays, informed me that I had cited myself: “’Matteo, Sante’ cited by ‘Sante Matteo,’” which struck me as odd and amusing enough to post on Facebook, where it elicited some witty and perceptive comments, to which I tried to reply in kind. The post (October 28, 2023) and the original comments are on my Facebook page.

The dialogue that resulted in the “comments” section seemed interesting enough to share with other friends who are not on Facebook. So, I made a copy to send to them and to keep for myself. As I re-read the comments and replies, other tangential ideas came to mind. To give voice to those related thoughts, I began adding made-up comments and replies.

Eventually, those “fake” accretions—consisting of questions or comments from and replies to fictional commenters, as well as altered and lengthened replies to the actual initial commenters—took over most of the narrative space and relegated the genuine comments to the edge, to serve mostly as an entrance into the meandering labyrinth that kept branching off in new directions.

Afterward, while composing this commentary about the genesis and evolution of the story, I realized that many of the ideas that crept into the story—seemingly out of left field (to deploy another negatively tinted use of “left” discussed in the text)—revolve around questions of identity that I’ve addressed in previous writing, both academic and creative.

My interest in the complexities of my own personal identity—who or what am I?—stems, no doubt, from being an immigrant, and especially one forced to migrate at a young age: taken away from my land of birth when I was about to turn ten, at the end of childhood and on the verge of adolescence. A substantial part of my identity—beliefs, sentiments, attitudes, mannerisms, biases, proclivities of all kinds—had been formed in one setting, whereas new segments of my personality—knowledge, truisms, prejudices, socio-politico-cultural awareness—were added to the half-formed “me” in an altogether different world. As a result, I was and have remained the shape-shifting product and servant of two different inculcative and proscriptive masters.

My childhood took place in a small agricultural community in southern Italy that had existed for many centuries as an isolated world unto itself, developing its own distinct dialect (derived from Latin and incomprehensible in other regions of Italy) and age-old beliefs, superstitions, customs, and traditions that hadn’t changed much since the Middle Ages. The stone-built houses had no plumbing or running water, no appliances. We had no cars, no television. Some aspects of that life are recounted in the stories “Bite in the Moonlight” (Coffin Bell Journal, Issue 2.2, April 2019). “Hold That Tail!” (The New Southern Fugitives, May 2019), and “Birds of Passage” (River River Journal, Issue 10, Dec. 2019).

In 1958, about a month before my tenth birthday, my mother, my younger sister, and I joined my father in the United States, where he had been for several years, initially admitted with a work visa as a mason skilled in marble work. The quota system obliged us to wait several years before we could be admitted with residential visas.

It was a magic-carpet voyage to another world (actually, even more wondrous than a magic carpet: an airplane! I think we might have been the first from our town to travel across the Atlantic by plane rather than ship), to a foreign land full of marvels: refrigerator, stove, carpeting, cars (with their own houses: garages!), central heating, and most magical of all, television; all immersed in incomprehensible gibberish, a new language that had to be learned from scratch. That experience and the changes it wrought in my now-split personality are recalled in a published memoir: “Coming to Dick and Jane’s America” (Ovunque Siamo: New Italian American Writing, Vol. I, Issue 4, March 2020).

In retirement, free to dabble in creative writing, I have mined the reminiscences of my Italian childhood and the experiences of migrating to a strange new land to trace and try to make sense of my meandering odyssey across the ocean of serendipity. Where did I start out? Where have I ended up? Where did I stop along the way? This new story published in Twelve Winters resounds with echoes from those previous efforts.

Another Platonic dialogue of sorts, this time in the form of an exchange of emails between a high-school student, who is working on a term project to explore career choices, and her uncle, who serves as a source reference. The uncle, a college graduate (who read Pirandello), works as a university custodian at night (for reasons he explains to his curious niece). One of the offices he cleans is that of an Italian professor named Sante Matteo, which prompts him to provide this account to his niece:

“When I clean their offices, I get glimpses of their lives: diplomas that show where they got their degrees; awards they’ve won; certificates for contributions to professional associations; mementos of travel and friendships forged abroad; the books on the shelves: some untouched, gathering dust, others piled up helter-skelter, borrowed from the library for the current (overdue) research project; pictures of family, showing their kids growing from year to year; papers stacked on their desk: exams and term papers to grade, drafts of essays, lesson plans, photocopies of interesting articles; even the trash in their garbage cans that tells me what they like to eat for lunch or for snacking—a lot of candy wrappers after Halloween!

“It’s fascinating how many parallel lives they lead—that we all lead, I suppose. The clues reveal the many circles of friends, colleagues, and collaborators among which they circulate: a galaxy of relationships contained in one small space. And I wonder: Is it the same person in all these roles? Or is the person different for each circle: perceived one way by students, another way by family members, yet another way by university colleagues; differently by professional acquaintances, by old high-school or college friends, and so on. How many faces or masks do they have?

“In that microcosm, the faculty office, many things come together and intertwine: the professional and the private, the social and the individual, the abstract (ideas) and the concrete (lesson plans, tests), the eternal and the momentary, the ideal and the practical. Those little spaces, little more than cubicles in some cases, contain traces of many separate yet related roles or incarnations.” (“To Thine Own Self Be True! But Which Self?” In Parentheses: New Modernism, 17 April 2021).

In another text, this one in the form of a monologue rather than a dialogue, and more precisely, a year-end letter of Season’s Greetings to friends, this passage could have been lifted from or immersed among the musings that are reiterated in “Mirror, Mirror in the Text”:

“[L]et’s dig up some etymological roots for the word that here seems to be in question: ‘identity.’ First of all, we should notice that even in the way we use it today — in its above-ground branches — the term is ambiguous. We carry an ‘identity’ card to prove that we are exclusively the individual we claim to be: a token of our uniqueness. And yet, the root of the word is ‘idem,’ Latin for ‘same,’ the opposite of ‘unique’ or ‘distinct,’ and, true to that root, the adjective ‘identical’ doesn’t mean ‘pertaining to one particular identity (ascertained by the ID card),’ but ‘exactly like something else, a duplicate’; hence, ‘identity’ means ‘resemblance’ and ‘commonality,’ antonyms of uniqueness.

“So, [we] run into [a] paradox. Our identity, what our ID card represents, consists of seemingly contrary properties: our commonality, our sameness with each other, as well as our difference from everyone else, our singularity.” (“Quantum Entanglement Between Doppelgangers,” essay with pictures about look-alikes, The Abstract Elephant Magazine, 15 March 2021).

The more immediate catalyst that sparked and fueled the impetus for this return visit to the question of “identity” was provided by current developments and discussions in society that evoke similar questions, doubts, and fears on a wider scale. My faux conversation echoes a widespread and intense societal preoccupation with questions of identity, whether articulated in terms of race, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation, religion, national identity, political affiliation, economic and class status, language, physical appearance, and other “identifying” features.

Debates about identity, furthermore, are part of larger concerns, anxieties, and arguments about truth in general, in all spheres of cognition: Does truth still exist? Can we perceive, if it does, and verify it? How can we tell the difference between real news and “fake news”? Can we tell if something we read or hear has been authored by a real person or by a program run by artificial intelligence?

All such concerns, doubts, and fears, both on a personal and communal level, are fueled, magnified, and exacerbated by our ongoing migration from physical space to cyberspace. Online, whether responding to emails or commenting on Facebook or another virtual platform, we can pretend to be someone or something different more readily and easily than in the physical world. We can choose when and how to answer and take our time to fashion our response and the impression it will carry. Before responding, we can look up information on any topic in Wikipedia or do a Google search and then pretend to know much more about any subject than we actually knew when it came up.

On the other hand, after looking up such new information, we really do end up knowing more than we knew before. By pretending to be someone different we have become different, both to the person we were trying to impress or fool and to ourselves.

In addition to being ever more uncertain about the authenticity of those with whom we interact through the internet and of any information that we receive through the media, our own identity, through such interactions, is in more flux and liable to manipulation, whether by other agents or by ourselves as we try to formulate appropriate responses and create attractive personas in various virtual environments. In a sense, we are becoming more “artificial” as individuals while we are becoming more apprehensive about the growing use of artificial intelligence in many arenas of our lives. Discussions abound in the media about the imminence of the “singularity,” the point when “artificial intelligence” programs will become so much more intelligent and thus more powerful than our “natural intelligence” and will take over running our lives and the world.

Is artificial intelligence to be embraced or feared? Is its continuous improvement and diffusion in more sectors of society inevitable, or can and should it be controlled, limited, or regulated in some way? Will it lead to the end of human history, or will it prove to be the next step forward in the expansion and evolution of civilization?

My story was published on Christmas Day (by pure serendipity, not because of a “Sante clause” in the contract). The next day, a news item in the Washington Post seemed to echo and magnify the issues I raised. It reported that Tuvalu, a sovereign island nation of 11,000 people in the Pacific Ocean that is sinking because of rising sea levels due to climate change, has reached an agreement with Australia to accept 280 Tuvaluans per year (for a curious example of life imitating art while art imitates life, look at Michael Washburn’s fiction, “Vanishing Island,” in the same issue of Twelve Winters Journal as my text: vol. III, 2023). The pertinent and striking aspect of the story is that, in addition to the geographical migration to another country, the nation and its inhabitants are also undertaking a virtual migration from physical space to cyberspace, from a corporeal to a digital identity:

“Tuvalu amended its constitution in October to state that the nation will maintain its statehood and maritime zones, meaning it will continue to assert sovereignty and citizenship, even if it no longer has any land.

“This follows an audacious initiative to become the world’s first digital nation, with the government last year announcing a plan to create a clone of itself in the metaverse, preserving its history and culture online so that people can use virtual reality to visit the islands long after they’re underwater.” (“A sinking nation is offered an escape route. But there’s a catch.” By Michael E. Miller, December 26, 2023).

Even though this news item did not influence the writing of my story, because I didn’t know about it yet, it seemed to embody and complement the topics I tried to address, and thus to serve as a more eloquent “commentary” on my piece than I can cobble together. The expectation and the actual planning for Tuvalu to become a “digital nation,” an artificial construct that exists at least partly in cyberspace rather than on an area of land, seems to me to encapsulate both the fears and hopes expressed in current debates about the danger and the promise of artificial intelligence.

As with other scientific discoveries and technological advancements–such as electricity, radiation, plastics, and atomic power, just to mention the first that come immediately to mind–we anticipate a future that, on one hand, will facilitate and improve our conditions and our lives, and on the other hand (or the other side of the same hand), also threatens to ruin our lives and the world if not kept under control—or even if it is kept under control but without all its manifestations and effects and potential consequences accurately foreseen. In the realm of computer technology and the rapid growth of artificial intelligence, the dilemma is particularly perplexing and compelling because it affects so many fields of human endeavor.

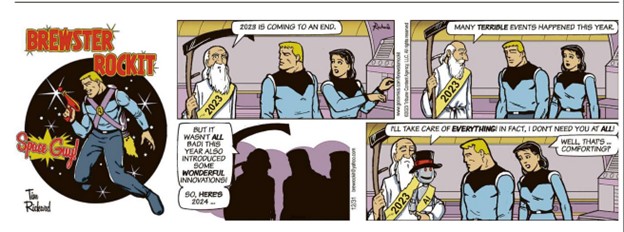

In the case of Tuvalu, the hopes and fears addressed in the dialogue about my name are extended to apply to an entire nation, albeit a very small one. But it, too, represents just a small stepping-stone in a vast ocean. Just a couple of days later, this “Brewster Rockit: Space Guy” comic in our newspaper took up the issue and extended its reach much farther, beyond the confines of the Earth:

▪ ▪ ▪

Sante Matteo was born and raised in a small agricultural town in southern Italy and emigrated to the United States with his family as a child. He maintained his ties to Italy as a professor of Italian Studies. He is currently Professor Emeritus at Miami University, in Oxford, Ohio, where he resides, reminisces, and writes. Stories, poems, and memoirs have appeared in The Chaffin Journal, River River, The New Southern Fugitives, Showbear Family Circus, Bark, Ovunque Siamo, Kairos, Snapdragon, and Dime Show Review. His story “Escape from Paradise” appeared in Twelve Winters Journal, Volume I.

journal | miscellany | press | podcast | team